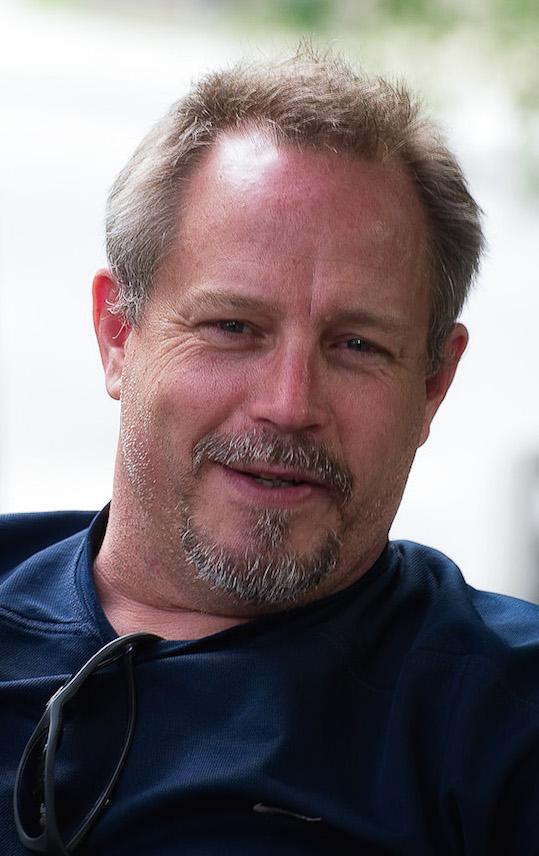

An Interview with Rory Miller

Interview by Gila Hayes

Unlike law enforcement, armed citizens don’t have use of force policies to rely on, yet we are bound by laws and court decisions. We have to work extra hard to understand what’s allowed because we don’t have explicit policies saying here is where you should use pepper spray, but it is OK to use a firearm here. Even legal use of force requires articulation to show why what we did was reasonable. Rory Miller and Lawrence Kane explained this well in their book Scaling Force. Miller, a retired sergeant from a large Oregon county corrections facility and widely-read author on unarmed self defense has put a lot of study into use of force issues.

Miller’s books and DVDs help ordinary citizens understand the dangers they face by categorizing violent assailants by goal and teaching realistic responses that are appropriate to the situation. Criminal assaults break down into social violence and asocial or predatory violence. While recognizing what drives an assailant aids in responding effectively, what implication does the type of violence we defended against have on legal jeopardy afterwards? Miller answered this and other questions when we had the opportunity recently to speak at length. He has much to teach, so we switch now to our Q&A format and get right to the point.

eJournal: Does knowing what motivates the criminal change our response and does that knowledge help when we explain why our self-defense actions were necessary?

Miller: Getting people to understand social and asocial is trying to level the playing field. Are you familiar with the concept of affordances? The idea is that how you see something absolutely controls what your brain is capable of doing with it.

If you raise cattle and slaughter them yourself, you don’t have to convince yourself it is a bad cow before you do it, you don’t give it an equal chance, you just butcher it. At the same time, when you look at a human, when you are seeing a human, all you can do with them is human things. Slaughtering does not come up on people’s radar, so they fight them; they struggle. When you see someone as a human, everything is about communication. You are trying to send them a message.

When humans look at other humans, there are totally different affordances based on how they see each other. That is the big division between social and asocial violence. When a criminal is seeing you asocially, he is not seeing you as a human, and he can do to you the things he can do to nonhumans, so he can hunt you, he can slaughter you, and he can use you as a toy. Until you grasp the fact that criminals are working from those motivations, they are not going to be doing any of the things you’re used to. If you are stuck on those scripts, you will be predictable and you won’t do him serious injury. He is unpredictable and he is willing to do serious injury, so the winner is pretty clear from the get-go.

The taxonomy you need for legal defense doesn’t break down along social asocial, but the affordances–what you allow yourself to do–will. If you’ve got a 300-pound guy with a knife that has you by the throat, it doesn’t matter why he is doing it. It doesn’t matter if he is doing it because he is so angry because he thinks you insulted his mom, or if he is doing it because this is what he does for fun. His motivation doesn’t change the amount of force you can use or whether force is necessary, but if you understand the affordances, my hope is that that gives you the chance to flip the switch and go asocial yourself when it is necessary.

eJournal: If we went asocial ourselves in order to stop an attacker, what legal implications may await when we get back from our visit to asocial behavior?

Miller: I taught use of force for the county for a long time, and I teach this now as part of my self-defense class, but I teach it as an articulation class. There are parts of the concept of self defense that do not function well in real life. Self defense is supposed to be a decision, but a lot of these things happen so fast that a decision is not going to be conscious. Everything is treated like you were doing it when you were not terrified, and being terrified changes your thinking.

Almost everyone actually makes good decisions under stress. Do you want to hurt anybody you don’t have to? Do you want to hurt anybody more than you have to? Do you ever want to kill anybody if there is any choice whatsoever? As soon as you are safe, do you want to keep hurting them?

eJournal: No, no, absolutely not and no, and I think those would be the answers of any Network member you might ask, as well.

Miller: Then your instincts are in line with the law. Those are the answers for almost any even vaguely socialized human being in our culture. If you’ve been raised in this culture, you have internalized the culture’s idea of right and wrong and fair. Most people make really, really good decisions, they are just crappy at explaining them.

Are you familiar with Sanford Strong’s Strong on Defense? It says one of the important things in self defense is your fear, but the best survival strategy is to turn fear into rage. Anger is one of the things that can really mess with your claim of self defense. How do you articulate that?

eJournal: That’s an issue and you said earlier that being terrified changes how you think. How can we survive being judged as if we are making conscious choices as the attack progresses?

Miller: Theoretically, self defense is supposed to be judged by somebody with your equivalent training and experience, but in practice it is always the people on the jury, the people who will hear your story, who will judge whether it is reasonable.

It comes down to your ability to tell the story so that they are actually in your head when it happened–because it was reasonable to you or you wouldn’t have done it. If you made a good decision and you articulated it correctly, you have to trust that people on the jury are smart enough to get it. Sometimes it takes a pro to help tell the story.

eJournal: We also worry about mistakes slipping in owing to the terror of the moment or the unpreparedness of the victim, such that one uses too much force for the situation or fails to stop using force once the danger is no longer immediate. This incident may be the one and only physical attack the victim has ever faced! What mistakes in judgment are common?

Miller: In my experience there are three places where people mess this up. They are actually fairly rare, but they happen. Number One: Two young guys are monkey dancing [posturing for social standing] and both are convinced it is self defense.

It’s like, “He said some shit first, so he started it.”

“He pushed me; he started it.”

“He punched me first; he started it,” and it was actually mutual combat the whole way.

The second, and possibly the hardest: It is over, the guy is down, you are in that wash of hormones and adrenaline and you want to teach the guy a lesson. It makes sense just in that second, so you throw in a couple of extra kicks. That is one that some people can get caught up in. I find that happens less with firearms, because you’ve got a little bit of distance.

eJournal: That’s what I mean when I ask about failing to stop once the threat is no longer immediate. Do you remember a few years ago when a Midwestern pharmacist shot one robber, chased another robber out of the store, then came back into the store, grabbed another gun and shot the first robber in the head five more times although he was already down bleeding on the floor? There are several theories and we’ll probably never know what actually happened. I do have to wonder if that isn’t a warning that yes, armed citizens can get caught up and go too far.

Miller: Yeah, it can happen if you get caught up and you chase the guy. Oh, and the third exception, before we forget. Sometimes people are trained to do things that are not legal. The classic in martial arts is to teach the student that after you put someone down you stomp on his head twice, “just to be sure.” Outside of internet warriors–the ones who are always spouting all the bad assed things they do–I’ve only ever seen, heard or read of one firearms instructor who taught shooting a disarmed and disabled person “in the face” as part of the technique.

eJournal: You wrote in Scaling Force that we need to enter the force continuum high enough to stop the attacker yet low enough to justify our use of force. How do we attain that correct proportionality?

Miller: You are doing it backwards. Most people are going to use the force that they subconsciously think is appropriate; they just will. The conscious mind isn’t fast enough to play catch up with this during self defense.

The force you use is triggered by your fear and it is always commensurate with your fear. I tell rookie officers, you use force when you get scared, you use enough force that you don’t feel scared and you keep using the force until you don’t feel scared any more. Every act of force is an admission that you were afraid.

It cannot be any other way. It is instinctive. It will not be out of sync with your fear; your fear just has to be reasonable. Once you dissect it, it almost always will be in sync, with those three exceptions we already talked about.

eJournal: What about moving up from physical force to guns without crossing the “objectively reasonable” line? Maybe the situation started with no guns involved and now our armed citizen has decided the danger is so extreme he or she must move up to deadly force with firearms in order to survive. An awful lot of in-the-news cases involve armed citizens who shot unarmed attackers. What’s your advice on the articulating how a threat escalated from push and shove intimidation into deadly force?

Miller: Guns are deadly force. In order to justify using a gun, you must be able to articulate why you reasonably believed you were under immediate threat for death or grievous bodily harm. And, though there appears to be an exception for Castle Laws and Stand Your Ground states, you want to be able to explain why you had no option. You couldn’t leave, or you tried to leave and were prevented. You couldn’t talk your way out, or you tried and failed. You can’t justify deadly force over ego: being insulted doesn’t do it. Having someone you care about insulted doesn’t do it. Getting fouled in a game of pick-up basketball doesn’t do it. Being shoved and intimidated doesn’t do it, usually.

Being shoved in front of a commuter train? That’s facing deadly force. A young woman being shoved into a closet, or being intimidated with a weapon and ordered to come quietly? That’s a different thing. But it goes to articulation. A woman saying that a big guy was pushing her, so she shot him will have trouble. The same woman who says, “He was twice my size and he said if I screamed he’d shut me up forever and then he started pushing me down a hallway and I knew if he got me in one of those rooms, no one could see or hear me, no one could help. If he pushed me into one of those rooms and shut the door, it was over…”

Same situation, but articulation makes a huge difference. And it’s not just the ability to tell the story. Practicing articulation is also a huge advantage in teaching yourself what to notice. The behaviors that go into articulation are the same behaviors that make the proverbial “red flags.” And almost all humans know them, but it’s rarely conscious.

eJournal: This sounds like it draws heavily on your experience working in corrections, a job regularly involving use of force and creating an unusual opportunity to learn from various incidents to explore what worked and explain the how, when and why factors.

Miller: Much as I hated writing reports at the time, it was critical to being able to pick apart my own subconscious and figure out where the decisions came from. It turned out that in almost every case, my subconscious was dead-on. If you just wrote, “I got scared, there was a blur, and the guy was down,” that was not going to fly. For me, it was sitting down and playing it over again in my head and picking out the clues. The first couple were just blurs; articulation was a skill I learned over time.

eJournal: I am interested in your transition from working with the inmates and teaching your officers, into your classes for private citizens. Have you identified aspects of use of physical force in self defense that the private citizen is most prone to misunderstand?

Miller: I think that the one universal is that people think fighting is self defense. Last year, in Germany I was told that I was going to be teaching a class to riot police, so I had a lesson plan all figured out. When I got there, the 30 people that showed up were from 13 different agencies and all had different policies and tools—some weren’t even allowed to arrest. Some of them didn’t carry weapons; some carried full SWAT gear. On the fly, I asked each student, “What do you want out of this class?” When it was all done, it was really easy to break down and I’ve been working with this ever since. It turns out there are only three things that you use force for:

- You use force to escape.

- You use force to put someone in a position to control or handcuff them.

- You use force to disable someone, to make them incapable of being more aggressive.

Within those three decisions, the body mechanics are different, the mind set is completely different, the ethics and rules and tools you’ll have are all very, very different.

They are three totally different types of force but not one of them has anything to do with fighting, squaring off and giving the other person a chance or turning it into an exchange of blows. All of your strategies, all of your thoughts, everything that goes to head-to-head fighting will actually hamper you if you need to escape, to disable, or put the person in a position to control.

eJournal: Since our members are primarily armed citizens, where does use of the firearm come in to those three basic reasons to use force?

Miller: The principles are the same. Guns are really important if you don’t have the physical strength; they are the big equalizer. Everything that we think and believe about equality could not have happened without firearms. The gun is one method that when you need things to be finished quickly, it is absolutely the right tool.

The one danger with firearms, and it is the danger with unarmed styles as well, if you think it is the ultimate solution that is not the same as thinking it is the ONLY solution. People get caught there if all they have is the top end and they have nothing below that. There is no good firearms solution for keeping your drunken friend from driving away from a party.

eJournal: True enough! We have a large number of members who read your work and rely on your experienced voice to give them reality checks like the things you’ve talked about with us today. I know personally, your books have done much to keep me on my toes. I am so pleased that you are part of our Network, and it is my hope we can come to you with questions and pick your brain from time to time.

Miller: Feel free. That is what brains are for.

__________

To learn how you can train with Rory Miller, visit http://chirontraining.com. For a full list of the many excellent books he has written, see http://www.amazon.com/Rory-Miller/e/B002M54CNW/.

Click here to return to July 2015 Journal to read more.